Welschriesling: The Pride of Moravia

Some grapes get all the credit. Others are left shrouded in mystery, concealed by obscure names, limited quantities, or an unknown genetic heritage. Subsequently, they rarely hit the shelves of the wine shops in the United States, and their reputation remains limited to within the wine’s original country of production. Although these cultivars may be wildly popular in a specific, localized area, foreign consumers and buyers like myself are ultimately left in the dark, unaware of the wine’s local reputation, incredible ageing potential, and exceptional quality.

Tanzberg Mikulov Ryzlink Vlašský ‘Goldhamer’ 2017

Let’s face it : Cabernet Sauvignon, Sangiovese, Riesling, Chardonnay, Nebbiolo, Pinot Noir, and other internationally recognized grape varieties are the moneymakers, commanding the attention of sommeliers, winemakers, wine buyers, and wine auctioneers from around the world. Garnering prices sometimes in the thousands of dollars, these wines certainly have their well-deserved, rightful place in prestigious cellars and auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

And I will not begrudge them, as for decades their legendary producers have worked tirelessly to shape their reputation and value. The sheer mention of one of these regions conjures up mental images of immaculately pruned vineyards, magical sunsets, and honeymoon vacation destinations. From Bordeaux, Champagne, and Burgundy, to Mosel, Tuscany and Rioja, these world class wine regions have proven that by finding the grape that is most suitable to their macroclimate and terroir, the resulting wines can be cherished for decades.

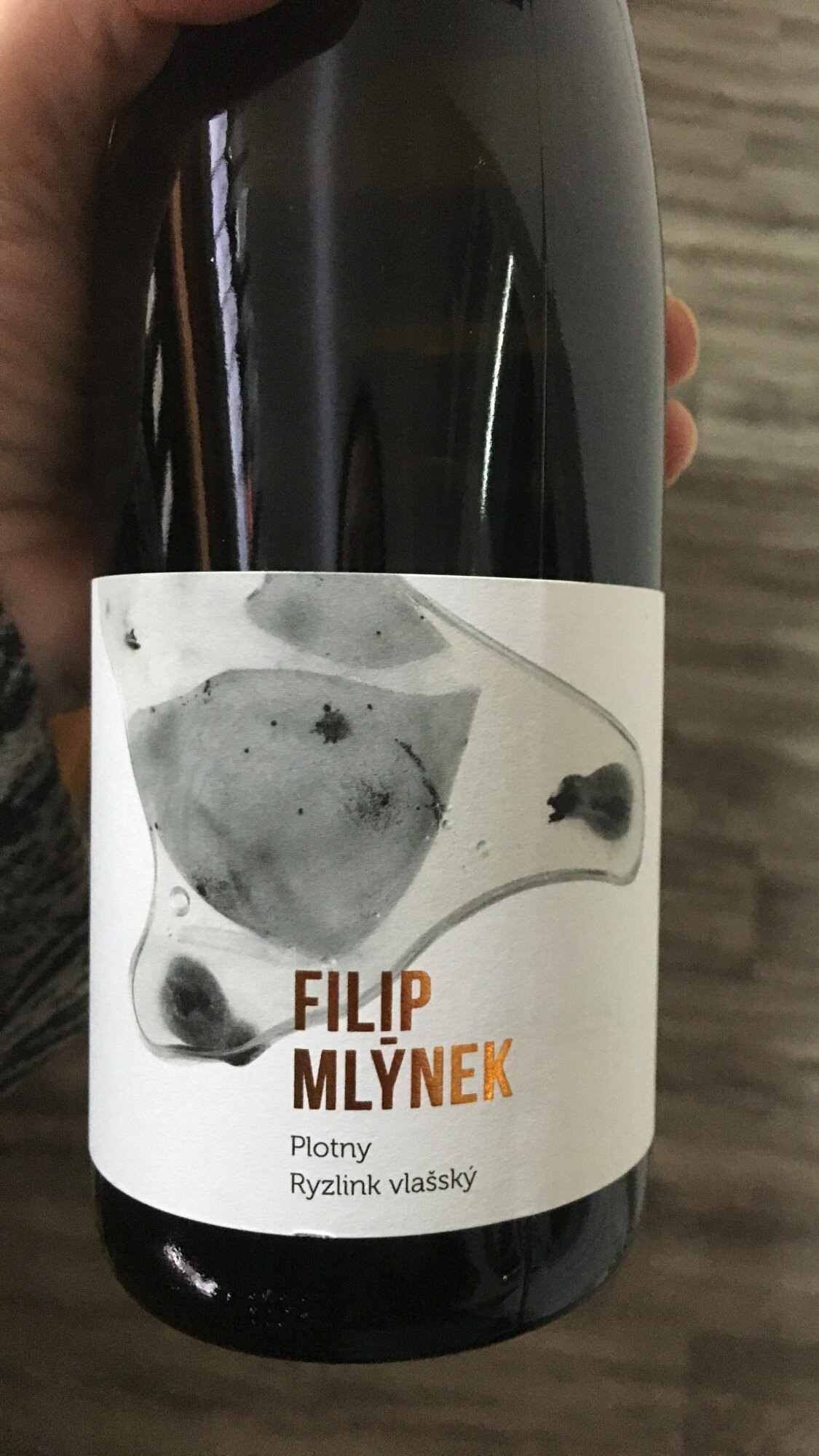

But I’ve always been one to root for the underdog, after all, I am a Mets fan…I love discussing the grapes that are less common, particularly those found in central Europe. For the past fourteen months in Brno, one grape in particular has stolen the show.

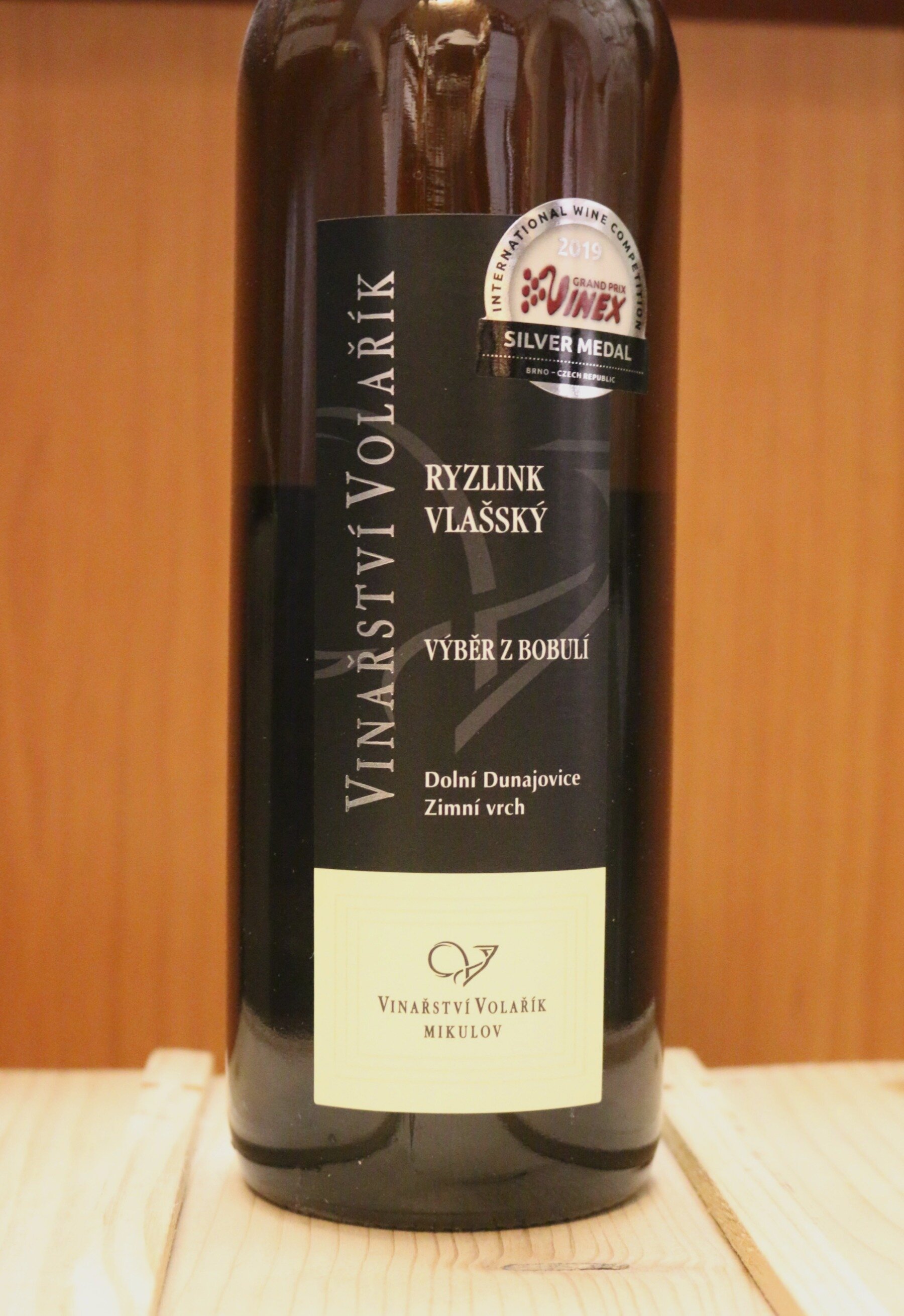

To be honest, at every tasting I attend, I’m secretly hoping to sample another style, to learn more about the grape’s exceptional range of flavors and aromas. Here in South Moravia, particularly in Mikulov and Dolní Dunajovice, it seems that practically every winemaker is planting it, and every consumer seems to be buying it.

This grape is Welschriesling, or as it is known in South Moravia, Ryzlink Vlašský.

Unfortunately, due to the lack of availability in the US market, I had spent the past ten years unaware of this grape’s prestige and popularity in central Europe. Yet in Brno, aka the heart of Czech wine country, Welschriesling is considered by many to be the national grape of the country, bolstering the reputation of this tiny region in international wine circles.

For me, Welschriesling is a chameleon, offering a plethora of terroir driven production styles, balanced with a firm backbone of fresh acidity and a palate rich with citrus and ripe stone fruit flavors. Additionally, when left in the hands of capable producers, these wines are truly ageworthy, evolving into a complex, enigmatic style that only gets better with bottle maturation.

Luckily, my feet are firmly planted in Brno, and I have broad access to learn about the range of locally-made, South Moravian Welschriesling. I am delighted to share some of my favorites here, to encourage fellow consumers to seek out these wines, because they are a truly remarkable reflection of terroir driven winemaking in the Czech Republic.

History of Welschriesling in Moravia

Pálava, South Moravia, Czech Republic

South Moravia is a region steeped in wine history and tradition. Nestled in the southeastern portion of the Czech Republic, it shares its borders with Austria and Slovakia. The vineyards are found on the western tip of the Carpathian mountains and at the foot of the Danube river. South Moravia is comprised of four distinct subregions, each with a particular macroclimate and soil composition. Vines have been cultivated here for centuries, as the area is truly ideal for viticulture and agriculture. Limestone and mineral rich soils, southern facing sloped hillsides, and increased sun exposure are a welcome relief for a cool climate reputed for its unpredictable growing season.

According to Vína z Moravy, Vína z Čech, vineyards have been planted in the region since the 3rd century A.D. Yet with the Roman expansion in the 12th century, the acres under vine were heavily expanded, mainly by the work of monastics. By the mid 14th century, the ruling Liechtenstein family further colonized the Mikulov region, planting vineyards in and around the Pálava Hills.

The Liechtenstein château in Valtice is a UNESCO world heritage site that can still be visited today. Underneath the château lies the National Wine Salon, where guests may sample over 100 wines from the region. This particular area was well suited for Welschriesling, as it prospered from the limestone soils and warmer, sunny days. The other variety planted was Grüner Veltliner.. We are Austria’s neighbor, after all.

Château Valtice

Unfortunately, the history of the grape is not as well defined as its own growing history in the Moravian region. Firstly, the official origin of Welschriesling has been quite disputed by wine professionals, as there is no specific evidence or written record that proves its native ancestry. Most researchers claim to have traced its roots back to Italy, where it is known as Riesling Italico, however this theory has never been validated. And although the name may suggest its relation to Rhine Riesling, this couldn’t be farther from the truth, as Welschriesling bears no DNA or genetic similarities to Rhine Riesling.

Welschriesling is planted primarily in central and eastern Europe, and goes by a multitude of synonyms. In Croatia, the grape is known as Graševina, and is the most widely planted white cultivar in the country.

Olaszrizling from Hungary

In Hungary, the grape bears the name ‘Olaszrizling’, translating to Italian Riesling. Italians refer to the grape as Riesling Italico, but there is no information or DNA evidence of its actual origin in Italy.

According to Jancis Robinson, in her fabulous book Wine Grapes, Welschriesling derives the name ‘Welsch,’ meaning “foreigner” as it refers to Wallachia, an ancient region in Romania. Yet this fact is also disputed, as the Romanians historically referred to the grape as Italian Riesling, and there is no evidence of the grape’s Romanian ancestry.

Here in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the grape is known as Ryzlink Vlašský, or its nickname, Vlašák, which translates to Walnut Riesling.

Yet no matter the name that it takes, this grape is indubitably revered in South Moravia, and I continue to be amazed by its complexity and range of styles. For this blog post, I will refer to the grape as either Welschriesling or Ryzlink Vlašský, and will omit its other foreign synonyms, as a way to eliminate confusion.

Welschriesling : The grape

All names and synonyms aside, Welschriesling is extremely well suited for the limestone sloped vineyard sites of Pálava, located in Mikulov. A late budding, fairly vigorous grape, it can be quite frost hardy and is able to withstand the sometimes harsh winters and unexpected spring frosts of central Europe.

The grape has a natural high acidity and sugar potential, particularly when treated on the vine with meticulous canopy pruning and/or a green harvest. In excellent vintages, the grapes are left to ripen further on the vine, sometimes into the latter half of autumn, lending itself to a half dry (polosuché) or even botrytized or sweet (sladké) dessert style of wine. The flavor profile of Welschriesling can vary tremendously, depending on the style of production, viticultural management, must weight upon harvest, and bottle maturation.

Welschriesling has certainly found its home in Mikulov, where it is classed as one of the six grape varieties permitted for VOC Mikulov. Although the term ‘minerality’ is highly debatable amongst Master Sommeliers and Masters of Wine as an aroma characteristic, I do find that Welschriesling does indeed pick up some of these wet stone, saline aromas, particularly in the bouquet.

The grape’s naturally high acidity helps to keep the wine balanced, and the style can be quite malleable, allowing the producer to mirror the climatic characteristics of each particular vintage. Some of the most sought after Welschriesling in the region are, in fact, the sweeter or straw wines, which garner a honeyed, luscious texture backed by a firm backbone of acidity, and can be bottle aged for over a decade.

Once in a Lifetime Tasting Experiences

My first experience tasting this grape was last winter, at the National Wine Salon in Valtice, a UNESCO heritage site that was once the majestic chateau of the Liechtenstein family.

Deep in the cellars of the Salon, along with my friend Victoria, I remember distinctly putting my nose into the glass of this unknown grape, and trying to decipher its key identifying characteristics.

Having never even heard of the grape before, I was determined from that moment on to learn more, as my inherent curiosity always gets the better of me. After that time, I spent hours scouring the Czech wine websites, studying various producers with hopes to enhance my own personal wine education.

For the past fourteen months, I have been researching and sampling Welschriesling, and I am delighted to share my experiences and favorite bottles here with you. And although I realize that a trip to the Czech Republic may not be on the top of everyone’s bucket list for wine destinations, I strongly encourage those in the wine industry to reconsider.

One of the most surprising Welschrieslings I have tried thus far in Brno, came from Kolby Vinařství, a winery located in Mikulov. This particular bottle was a 2009 Late Harvest (Pozdní Sběr), Half Dry (Polosuché) Ryzlink Vlašský that showed a deep golden color in the glass and an expressive, broad flavor profile. Kolby’s Welschriesling vines were initially planted in 1984 (so it shares the same age as yours truly), and currently occupies 8.5 hectares of their entire vineyard.

I was a bit skeptical upon opening the bottle, not knowing how a 2009 Welschriesling would hold up after 10 years, but I could not have been more pleased. The nose exploded with pronounced tertiary aromas of honey, beeswax, almonds, and baked apricots, while the palate showed bright acidity and a lengthy finish. This bottle was quite a treat, and certainly provided me with an unforgettable tasting experience.

Kolby Vinařství Ryzlink Vlašský 2009

The Future of Vlašák

In my opinion, Ryzlink Vlašský will catapult the region’s popularity, setting the spotlight on terroir driven wines with complexity and character. Thanks to publications like Decanter, Wine Spectator, Wine Folly, and education programs like WSET and CMS, consumers around the world are becoming more savvy and knowledgeable. Thankfully, more Moravian producers are finding export companies who are willing to engage with this fairly unknown wine region, and the results have been extraordinary. Competitions in the Finger Lakes, NY and San Francisco, CA are proving that South Moravia is a wine region to be recognized, and I can only imagine the country’s wine potential.

Vican Rodinné Vinařství Ryzlink Vlašský 2017

As a former sales employee in the States, there is a current movement to seek out those hard to pronounce, rare grape varieties hailing from exotic regions in central and eastern Europe. Personally, I feel that with the broad range of production styles available with Welschriesling, there would be something for everyone. Additionally, the grape has the capability to withstand spring frosts in the vineyards, and has proven to be fairly hearty on the vine, lending itself well to the unpredictable growing seasons ahead. I for one, am certainly going to keep an eye on this grape in the foreign markets, as its unique qualities and ageing potential can make it a powerhouse in key sales markets, particularly in the sector of sweet dessert wines.

South Moravia is quickly becoming the newest hot spot for sommeliers, wine professionals, bloggers, and foodies. Even Madeline Puckett from Wine Folly is digging the region’s wines!

So book your flight, and join me in Brno to discover the multitude of expressions of Ryzlink Vlašský.